Bordeaux vs Burgundy: The Eternal Rivalry!

I recently had an interesting conversation about Bordeaux bashing and the comparison between Bordeaux and Burgundy, which inspired me to create the illustration above and write this post.

We discussed the various problems that both regions have faced over the last decade and attempted to compare them, ultimately trying to dispel the misconception of rivalry between the two.

Starting with climate change, then delving into administrative, market & economic challenges, and concluding the conversation by exchanging our views and opinions about the region's respective images, reputations, and pricing strategies in today's world.

In this post, I am retranscribing that discussion, providing further details and facts with my own views, opinions, and perspectives, as I typically do.

Note: Some readers may disagree with my opinions or how I present them in this post, particularly about Bordeaux. However, I am a native of Bordeaux and have been promoting the region's wines through tasting, visiting, buying, selling, serving, and drinking them for over 30 years across three continents.

Therefore, please read carefully before judging, as I have nothing against Bordeaux and am not trying to be disrespectful; on the contrary, I love Bordeaux and its wines. I aim to present the facts as they are, stating them as accurately as possible. Ultimately, my voice and words are just one among many that have been calling for changes for years, urging Bordeaux to adapt to shifting market conditions, update its image, and find innovative solutions for a more resilient future.

Climate change and weather patterns

Bordeaux has a milder, more humid maritime climate over a generally flat topography (especially the left bank, as the right bank has some hills and valleys) influenced by the Atlantic Ocean, the Garonne and Dordogne rivers, and the Gironde estuary, which moderates the weather, resulting in mild winters and warm summers, with some heavy rainfall usually in winter and spring. It can also rain during the summer, in the form of light showers or occasional thunderstorms, but rainfall typically decreases from June to August.

Although Bordeaux usually enjoys beautiful, warm, and dry "Indian Summers," the rain that sometimes occurs during the harvest, typically late September or early October, is the fear of all producers, as light occasional showers may benefit the vineyards and the grapes, but days of rain at that time can also be disastrous. The moderating influence of the ocean, the estuary, and both rivers helps create a consistent, warm climate, which, combined with the topography and the gravelly soils on the Left Bank and clay-rich soils on the Right Bank, is suitable for late-ripening grapes, such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Merlot.

On the other hand, with its cooler, continental climate, Burgundy experiences more extreme temperatures, with cold winters and hot summers. The climate is more unpredictable and challenging, often bringing cold winters and the threat of spring frost. Nonetheless, summers tend to be dry and sunny, which is essential since many of Burgundy's most prized vineyards are located on slopes facing east or southeast. This positioning maximizes the morning sun and provides plenty of light for grape ripening, until late afternoon when the sun passes behind the mountain to the west, casting shadows over the vineyards.

Compared to Bordeaux, Burgundy is characterized by rolling hills and gentle slopes that create a mosaic of diverse vineyard sites and microclimates. Its defining geological feature is a limestone-rich soil, which is a result of ancient marine deposits from a Jurassic-era lagoon, often mixed with marl and clay, contributing a distinctive minerality to the wines. This makes it an ideal region suitable for delicate, early-ripening varieties, such as Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

In terms of weather patterns, like most regions in France and around the world, both Bordeaux and Burgundy have experienced the accelerating effects of climate change in their own unique ways, particularly over the last decade. In fact, they have experienced them for over 40 years, as the acceleration of these effects occurred at the begining of the 80s, and each decade has been hotter and thus more challenging than the previous one, ever since.

This trend of increasingly warmer decades has been a consistent pattern since the 1980s. The rate of warming has sped up, with the rate for 1981-2020 about 0.4°C per decade (that's +1.2°C in 40 years), compared to earlier periods. The global average temperature has risen significantly over the last decade, with 2011-2020 being the warmest on record, approximately 1.09°C above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial average, according to the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change).

And for the 2020s, each year has been hotter than the last so far, with 2024 being the hottest year on record (partly due to a strong "El Niño" event). Global temperatures have exceeded the pre-industrial average by approximately 1.55 degrees Celsius, marking the first time this 1.5°C threshold was crossed in a calendar year.

The increasingly unpredictable weather patterns have resulted in more frequent challenges, including frost, hail, storms, rain, floods, and droughts, in both regions. These shifts and conditions, notably higher temperatures, more frequent droughts, and severe heatwaves, disrupt the vine's growth cycle during late spring and summer, resulting in lower yields, premature grape ripening, and/or over-ripening.

Meanwhile, more frequent hail and rainstorms, as well as floods and high humidity, in spring, summer, and early autumn during harvest time, increase the risk of damaging the vine shoots, lowering yields, and dilution, as well as diseases such as downy mildew. This variability has made it more challenging for winemakers to maintain consistent quality, resulting in increased vineyard work and labor costs, and requiring greater attention and vigilance to protect the harvest.

These situations also require financial means to cover the costs of machinery, products, and labor, among other expenses, which have increased due to higher demand in recent years, resulting from the higher frequency of these events and putting producers in a dire situation.

Climate change and changing weather patterns are concerning issues because they directly affect the vineyards. However, Bordeaux and Burgundy also face other challenges, such as administrative, market, and economic issues.

Let's begin with Bordeaux since it's a region I know better than Burgundy.

Administrative, Market & Economic challenges

Bordeaux has struggled with declining consumer demand, particularly among younger generations, due to shifts in consumer habits, high prices, and changing financial opportunities. It also suffers from its outdated, traditionalist, and aristocratic image, and has significant issues with its "En Primeur" system and classification.

Bordeaux "En Primeur" wines are overpriced, stagnant, and disconnected from release prices, leading to reduced demand and a flooded secondary market. Recent vintages have frequently been launched at prices that are too high, disconnected from what consumers are willing to pay.

This overpricing has caused demand to stagnate, with many wines from recent vintages trading at prices lower than their initial release prices, leading to unplanned unsold wine stocks. As a result, rising storage and borrowing costs put financial pressure on the system, especially when stock remains unsold and loses value while stored.

Despite some late efforts to lower the release prices for the 2024 vintage, the high release prices of previous vintages, such as recent ones (2021, 2022, and 2023), and the price stagnation or decline in the secondary market, have resulted in wineries and merchants alike still having large stocks of unsold wine. Weak demand and unfavorable global market conditions created a situation where buyers are unwilling to pay high prices for these wines.

The system's reliance on traditional intermediaries, such as courtiers and négociants, is seen as an outdated, lack of transparency model that creates barriers between producers and consumers, resulting in financial strain and alienating modern consumers.

The system, which sells wines "en primeur" before they are bottled, has been undermined by the availability of back vintages that are now selling for less than release prices, making consumers wary of buying unfinished wines.

Other issues include the long wait for delivery, uncertainty about the final wine quality before bottling, and a shift in top producers' preferences for direct-to-consumer sales or subscription models, which challenge the traditional model's long-term viability.

Bordeaux classification problems stem from the 1855 classification's static nature, which fails to account for over 170 years of evolving quality, winemaking, vineyard management, and ownership changes, leading to a disconnect between official status and current quality. Key issues include outdated rankings, the omission of Right Bank wines, market distortions where status and prices outweigh merit and even quality, confusion caused by younger and more dynamic classifications such as those in Saint-Émilion, and controversies surrounding the rankings, demotions, and withdrawals from the system.

The 1855 classification has remained largely unchanged since its creation, despite significant advancements in winemaking, vineyard management, and shifts in estate ownership, quality, and size over the past 170 years. Many estates have significantly improved their quality, yet their classification has remained the same, while some classified estates may have declined relative to non-classified ones.

The 1855 classification also excluded Right Bank wines, such as those from St-Emilion, and other wine regions from Bordeaux. The staticity of this classification system creates market confusion and leads to status mattering more than the actual wine quality, causing price distortions.

Additionally, wine styles in 1855 were quite different from those today, featuring lower alcohol levels and less tannic wines. Bordeaux wine's alcohol content has increased from traditionally lower levels, around 12-12.5%, to modern averages closer to 14%.

This trend has been gradually driven by various factors, including rising global temperatures—especially since the mid-1980s, around 1985 and 1989—leading to increased grape ripeness and higher sugar content. It has also been influenced by changes in winemaking techniques, vineyard and cellar management, and consumer tastes shaped by influential wine critics, which drove demand for more powerful wines and encouraged growers to pursue higher alcohol levels, longer oak ageing period, and the use of more toasted new oak barrels (a trend coming from the US in force in the 80s and 90s).

This trend also introduced or further developed the concept of second and third labels, as well as the second and third wines made from grapes grown on younger vines or from vineyard sections that didn’t quite meet the standards of the Grand Vin, but still received the same meticulous care and winemaking process.

This allowed the château to enhance the quality, complexity, and aging potential of the Grand Vin, while offering wines of similar quality that were less complex and more suitable for early drinking. This created options for wines at different price points and quality levels. This practice, still used today, also helped generate revenue to support the estate while waiting for the release of the Grand Vin.

For example, Château Latour created its second wine, "Les Forts de Latour," in 1966, and its third wine, "Pauillac" de Latour, in 1989 (or 1990, depending on the source).

Moreover, the classification is outdated, as many estates have changed hands and vineyard sizes have increased dramatically since 1855. Some small estates have been merged into larger ones, while others have been acquired by wealthy individuals and large corporations. Although these mergers aimed to create larger, more economically viable properties, improve production capabilities, enhance reputation, and diversify operations for greater financial and social success, the outcomes often varied, impacting, in some cases, both the quality and consistency of the wines, despite overall improvements in production.

As for the other classifications, while newer, the Graves Classification, established in 1953, revised in 1959, and refined by the creation of the Pessac-Leognan appellation in 1987, offers no quality distinction, listing all classified estates with the same status despite inherent quality variations.

The Saint-Émilion classification, established in 1955 and revised in 1958, is periodically reassessed roughly every 10 years. The list was updated in 1969, 1986, 1996, 2006, 2012, and 2022. However, it has faced issues with a confusing A/B rating system and controversy over rankings, demotions, legal challenges, and even withdrawals by top estates, like Château Cheval Blanc and Ausone in 2021, followed by Angelus in 2022, due to disagreements with the system, which they felt had become a source of conflict and instability instead of progress.

Some estates, with strong brand recognition, no longer rely on official classifications, further weakening the system's relevance. For example, Château Lafleur announced just a few days ago that it had left the Bordeaux Appellation System and revoked its status as a Pomerol and Bordeaux wine, selling all six of its labels as Vin de France from the 2025 vintage onwards. This move responds to the accelerating impacts of climate change and the increasing restrictions imposed by the Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée/Protégée (AOC/AOP) system, as mandated by the Institut National de l'Origine et de la Qualité (INAO).

More estates may follow if things don't change and the restrictions are not relaxed in the coming years. It is too soon to figure out whether they were right to do so. Some take it as a threat to the appellation; others applaud their bold decision to step out. Good or bad thing? Time will tell.

Additionally, over the past 25 years, the rest of the world has followed suit in producing wines, with more than 80 countries (out of 195 worldwide) now making their own, resulting in overproduction, increased national consumption, and reduced imports from other countries. China, for example, which used to import countless containers of Bordeaux wines in the 2010s, is now relying more on its own wines. The problem is that high demand from markets like China in previous years supported increased Bordeaux release prices for certain vintages, but this is no longer the case.

Climate change, geopolitical situations, financial crises, global inflation, taxes, tariffs, overproduction, and other factors, such as changes in consumption habits and growing health concerns in the young generations, have led to a global surplus of wine and unsold stocks (in both wineries and merchants' warehouses around the world), weakening the market.

As a result, facing an excess of wine, some Bordeaux producers have turned to diversifying their crops and offering products like zero- or low-alcohol alternatives, more appealing to a younger audience, to meet demand, or, in the worst cases, have chosen distillation or even uprooting vineyards to control their supply, focus on other crops and avoid having to shut down.

The uprooting of vineyards in Bordeaux is being carried out in accordance with a French government-funded program aimed at addressing overproduction, declining domestic and international demand, global inflation, high prices, financial priorities, health concerns, and shifting consumer preferences that favor other beverages or simply can no longer afford wine in their monthly expenses. The program offers subsidies to winemakers for removing vines and repurposing the land. This strategic adjustment aims to stabilize the Bordeaux wine market by reducing supply and refocusing on higher-quality production.

To summarize and conclude, over the past decade, Bordeaux wines have faced significant challenges, including the severe effects of climate change, which have led to volatile vintages and increased production costs. Additionally, there has been a global decline in demand, particularly from China, and an oversupply of red wines resulting from the downturn in domestic and export markets.

All these factors (cited above) have resulted in falling prices for many wines, market saturation, and even government-funded vineyard uprooting programs aimed at addressing the imbalance between supply and demand. The continuously increasing restrictions imposed by the Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée/Protégée (AOC/AOP) system, as mandated by the Institut National de l'Origine et de la Qualité (INAO), are outdated, too strict, unflexible, and insufficient to address many of the challenges faced by vignerons.

Therefore, yes, Bordeaux wine is experiencing a period of significant decline, characterized by decreasing sales, falling prices, and a record-low harvest in 2024, caused by disease and uprooting programs. The crisis stems from years of overproduction, resulting in strategic supply cuts and reduced vineyard acreage to combat declining demand, particularly for red wines, as well as shifting consumer preferences.

Being a Bordeaux native, I have serious concerns about this situation. Although I have spent my 33-year career promoting Bordeaux wines, including both small and large châteaux, I can't help but think the situation is dire and could cause long-term damage to the vignerons, the region's economy, and the wine industry as a whole. In the meantime, I hope for better days ahead. Wishing strength and courage to all Bordeaux vignerons.

Now, let's review the administrative, market, and economic challenges Burgundy has faced over the past decade, while comparing them to those of Bordeaux.

While Burgundy faced challenges with high prices and the perception of artificial scarcity, despite its focus on small-scale luxury, it is not performing as poorly as Bordeaux. In fact, although both regions have encountered difficulties in the global fine wine market, particularly over the past five years (the post-COVID period has been challenging for all wine regions in France and around the world), Burgundy has shown signs of resilience and has even outperformed in recent years due to demand for its unique, rare wines. In contrast, Bordeaux has experienced a decline in market share, as well as fewer en primeur campaigns.

Although both regions are currently facing a general market slowdown, Burgundy is regarded as a more resilient and desirable market for collectors, especially in the high-end, collectible segment. In a supply and demand-driven market, the limited production of Top Burgundy wines indeed makes it a more valuable investment over time, compared to Bordeaux, which produces larger quantities that can be easily found in the market decades after their release, even for the most sought-after chateaux in excellent vintages, thus limiting the price appreciation over time.

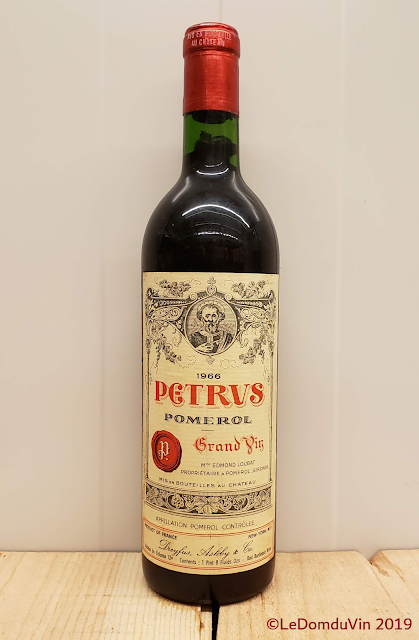

While some producers only make a few thousand bottles of "Premier Cru" and even fewer of "Grand Cru," more renowned Bordeaux Chateaux, whether classified or not, such as "Petrus," already produce around 30,000 bottles annually from 11.3 hectares. This is relatively small for Bordeaux, but still quite significant compared to Burgundy, where, for example, Domaine de la Romanée-Conti produces approximately 5,000 to 6,000 bottles of Romanée-Conti per year from its 1.8-hectare vineyard. Only the Bordeaux properties nicknamed "garagists", such as "Le Pin", usually produce less than 10,000 bottles per year.

The Bordeaux region is a significantly larger vineyard area than Burgundy, with larger average property sizes. Bordeaux boasts nearly 110,000 hectares (up to 125,000 hectares depending on the source) of vines and approximately 6100 wine estate owners and growers (+ 33 wine cooperatives regrouping an additional 2500 growers/producers), with a typical estate covering about 17 hectares. These figures reflect the diverse landscape of the region, which encompasses both large, internationally owned companies and smaller, family-owned estates that have been passed down through generations.

In contrast, Burgundy's vineyard area is significantly smaller, at roughly 25,000 hectares in AOC vineyards (out of a total of 29,500 hectares planted), shared among about 4,000 domaines and cooperatives. In summary, Burgundy's vineyard area is roughly 4.5 times smaller than Bordeaux's, even though it has more than half the number of Bordeaux producers.

Consequently, the domaines tend to be much smaller too, as 85% of its domaines are under 10 hectares, typically family-owned estates that have been passed down through generations. Compared to Bordeaux, which has a more stable system of inheritance, Burgundy suffered from its vineyards being divided among generations, thus increasing the scarcity of bottles and the prices from the top producers.

Over the last two centuries, Burgundy properties, particularly vineyards, have been divided among generations primarily due to the Napoleonic Code, which mandated equal inheritance among all children, resulting in the continuous subdivision of land parcels with each passing generation. This law decreed that property must be divided equally among all heirs, breaking from the previous system, where only the eldest son was entitled to inherit.

This practice, which began in the early 1800s following the French Revolution, created the complex, fragmented ownership structure seen today, where even large Grand Cru vineyards, such as Clos de Vougeot, are divided into numerous small, independently owned plots (approximately 50 hectares, or 125 acres, split into over 100 parcels owned by about 80 proprietors).

Despite what some well-known hyphenated family names on labels might suggest—like Fontaine-Gagnard or Bachelet-Monnot—and the common misconception that marriages between Burgundy heirs are mainly meant to preserve vineyards, as shown in fictional works like the film "Back to Burgundy" (Ce qui nous lie), to address inheritance tax issues and consolidate family holdings, this is not usually the case.

In reality, the primary challenges to keeping vineyards in the family are inheritance taxes and land fragmentation resulting from Napoleonic inheritance laws, which impose significant financial burdens and create complex legal situations for heirs.

When family estates are passed down, high inheritance taxes can force heirs to sell all or part of the business to cover the costs, especially if the property's value has increased significantly. The combination of expensive land and the need to pay taxes creates heavy financial pressure on families, sometimes causing them to sell to foreign investors.

That's why marriage is sometimes seen as a way to link two separate family vineyards, creating a larger, more sustainable estate that's less likely to be sold. By marrying, one heir might gain access to the other family's financial resources, which could then be used to cover the hefty inheritance taxes that might otherwise force the sale of their own family's vineyards. If marriage isn't planned, heirs can agree to manage the property jointly, or one heir can purchase the shares of the others.

Fortunately, recent changes to French inheritance laws and tax regulations, particularly the higher exemption limit, are helping Burgundy vintners preserve their family vineyards. If the situation becomes truly dire, external investment might be the only option remaining. While sometimes controversial, bringing in outside investors can provide the necessary funds to pay taxes and sustain the business.

Like Bordeaux, Burgundy has also faced climate change-related challenges over the past decade, including spring frosts and excessive heat, which have led to significantly reduced and fluctuating wine yields. Other issues include supply shortages caused by these low yields, higher costs for new farming techniques to fight climate problems (such as expensive "candles" for frost protection), shifts in market demand for their wines, and the increasing influence of outside investors owning vineyards, which changes the traditional grower-proprietor model. Unfavorable weather conditions, including those driven by a changing climate, have increased disease pressure from problems such as downy mildew in some years.

All these factors have significantly increased Burgundy's prices over the past decade. Generic Bourgogne has risen by 50-60%, while top-tier Grand Cru wines have doubled or more. This price surge is fueled by consistently low production, strong global demand for Burgundy's reputation and quality, and the scarce supply of wines from highly sought-after "cult" estates. Moreover, compared to Bordeaux, active auction markets and speculative collecting of premium Burgundies have further boosted prices.

In short, Burgundy prices have skyrocketed over the last decade, while those of Bordeaux have plummeted. Yet, as Burgundy wine prices soar, we could be inclined to think that people might return to Bordeaux for better value. A situation that may entertain the illusion of rivalry between them.

Ironically, even though Bordeaux offers more choices, greater availability, and often better quality than Burgundy in the under €20/bottle range, people still favor Burgundy wines, despite often coming with a higher price tag compared to those from Bordeaux.

On average, Burgundy bottles tend to be more expensive than those of Bordeaux, especially at the high end, because Burgundy's limited production and high demand drive prices upward. While Bordeaux has many affordable entry-level options, Burgundy offers fewer, and even basic "Bourgogne" wines often cost more than the entry-level Bordeaux equivalents.

The average price for a bottle of Bordeaux wine is usually around €10-15. However, the price can vary significantly based on factors like the specific château, vintage, vineyard quality, and whether it's a prestigious classified growth or a more accessible appellation.

In an ideal world, the quality and characteristics of a given year (the vintage) should significantly influence its price; however, this is not always the case. For example, the 2021 Bordeaux vintage was characterized by cooler conditions, resulting in wines that are more approachable but of lesser quality than the previous three vintages (2018, 2019, and 2020).

However, Bordeaux made a major mistake, as the 2021 "En Primeur" release prices were far too high for the quality and expectations of this particular vintage, generally similar to or slightly lower (not even 10% less) than the 2020 vintage, with some estates releasing at the same price point, while others offered price decreases. This resulted in buyer dissatisfaction, poor sales, a loss of credibility, and an additional reason to contribute to the phenomenon of "Bordeaux bashing."

The pricing strategy is another big difference between the two regions. While Burgundy remains relatively consistent in adjusting its prices depending on the quality of the vintage, production, and overall market demand, Bordeaux consistently increases its prices from one year to the next.

In recent years, Bordeaux en primeur (EP) prices for the 2018-2024 vintages have generally seen increases, criticism, and a disconnect from secondary market prices, with a market trend of prices falling in the years following their release, resulting in the dire situation we know now, with concerned buyers reluctant to buy or invest in Bordeaux any longer.

In short, as 2018 was a great vintage, the EP release prices were significantly higher than in 2017, which was a much lesser vintage. Then, 2019 was also a great vintage, but not as praised as 2018, showing prices similar to or lower than those of 2018. Then 2020 arrived with a higher quality than 2019, and despite a handful of Châteaux setting the right example by releasing at a slightly lower price point than 2019, the rest of Bordeaux raised its prices again. 2021 was a lesser vintage than the previous three, but Bordeaux still chose not to significantly lower its prices compared to 2020. Then 2022 emerged as a "super vintage", one of these "vintage of the century" (the umpteenth since the beginning of this century), and prices went even higher than those of 2020.

At this point, due to COVID-19, inflation, the global financial crisis, shifts in consumer habits, and other factors—including the outrageously high EP release prices, which caused buyers' dissatisfaction and confusion—Bordeaux sales and reputation declined sharply, leading to a drop in the market. Bordeaux attempted to significantly lower its prices for the 2023 vintage, which was of lower quality than the 2022 vintage, in an effort to revive the market, but it was unsuccessful. Then, in 2024, prices were even lower than those of 2023, addressing buyer caution and the high market prices of previous years. Still, some châteaux managed to set prices completely disconnected from the quality and expectations of the vintage once again.

As a visual is worth a thousand words, I have created the table below to illustrate the rollercoaster inconsistency of Bordeaux prices over the past decade (2014-2024). It demonstrates, as mentioned many times before in previous posts on the same subject and about scores and ratings, that Bordeaux's incoherent prices are based solely on the quality and release price of the last vintage(s), without considering the intrinsic quality and value of the wine or the vintage itself.

I used Mouton Rothschild as an example because it is part of the first growths, which typically show the most inconsistency in their prices. As part of the leading Chateaux (the so-called "locomotive of Bordeaux"), they establish the reference price points everyone else follows. They should therefore set a better example for all the others. But, except for a few rare exceptions, they usually don't.

Don't you agree? Look at the table again and tell me. Isn't it ridiculous? It is. For example, 2021 was released at 2.9% cheaper than 2020, while 2020 is a far better vintage than 2021, so why is the 2021 so expensive? 2021 was released at a more expensive price than 2018 and at the same price as 2016, which are also considered far better vintages. And why was 2022 released at such a significantly higher price than 2018 and 2020, which are also great vintages? Was it worth it to deserve being sold for roughly 100 Euros more? I don't think so. Bordeaux should not be surprised if buyers are no longer willing to pay these prices. They shot themselves in the foot by doing so.

I really think that Bordeaux should have reviewed its pricing strategy more than a decade ago and been more consistent over the years by adopting more reasonable "fixed" prices. For example, Mouton Rothschild should set its price between €380 and €420 in regular years (2015, 2018, 2020), then lower it between €310 and €350 in lesser years (2014, 2017, 2021, 2024) (or lower if they feel like it), and increase it between €450 and €480 maximum in greater years (2016, 2022), not go over €500, otherwise, there is no limit?

I understand that the cost of life and production may have increased significantly since the COVID pandemic in 2020, due to all the challenges and reasons mentioned above (COVID, climate change, inflation, global financial and commercial crises, taxes, tariffs, wars, geopolitical issues, shifts in consumer preferences, health concerns, global overproduction, rules, restrictions, laws, etc.).

However, despite efforts to substantially lower the prices of the 2023 and 2024 vintages to revive the market and restore buyer confidence in a market already weakened with declining sales over the last 3-4 vintages due to lack of demand and high prices disconnected from what consumers are willing to pay, the top Châteaux should communicate with each other and adopt a better market pricing strategy. They should avoid penalizing buyers with inconsistent prices and instead return to more reasonable pricing if they want Bordeaux to experience a renaissance, change its image, and thrive again, as it once did.

The main problem with Bordeaux isn't the top 500 Châteaux, the so-called "locomotive of Bordeaux," which are the ones that sell the most and offer wines ranging from €50 to over €500 per bottle (release price), representing Bordeaux's image worldwide. These will always sell one way or another.

The main issue with Bordeaux is the problems faced by the 6,000+ other Bordeaux estates, producers, and growers, mostly offering wines below €50, with a large majority selling only between €3 and €20. They struggle to sell their wines in the shadow of the famous ones, which tarnish Bordeaux's reputation with high prices and wrong, outdated image and marketing strategies. Most people think Bordeaux wines are expensive, the top ones, yes, but that is not the case for a vast majority of Bordeaux wines.

As a result, there is an ocean of wines, bottles, and labels that have seen their market shrink both locally and internationally, and their prices fall despite all the climatic, political, financial, and economic challenges they have faced over the last decade.

********work in progress********

Bordeaux and Burgundy are often seen as rivals. The rivalry between them is a centuries-old debate driven by their different philosophies, grape varieties, and winemaking styles.

Still, "rivals" is a strong word; I prefer to call them friendly competitors because, in the end, they target similar but slightly different types of consumers, collectors, investors, and markets.

This friendly competition, often viewed as a reflection of the broader French spirit—Bordeaux's bourgeois influence versus Burgundy's more aristocratic, sensual nature—provides wine enthusiasts with a rich choice between power and finesse, structure and delicacy, drinkability and age potential.

It's a healthy competition where they observe and challenge each other to improve, despite their differences. Because there are no two wine regions that could be more different than these two.

Their philosophy differs in that Bordeaux focuses on blending grapes to create complexity and structure, with styles such as robust Cabernet Sauvignon-based reds from the Left Bank or Merlot-dominant wines from the Right Bank. Meanwhile, Burgundy emphasizes expressing a single vineyard's unique characteristics through single-varietal wines, highlighting the profound influence of terroir.

Their grape varieties differ as Bordeaux is known for its bold, complex blends, usually featuring Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. At the same time, Burgundy is renowned for its elegant, terroir-driven single-varietal wines, particularly Chardonnay for whites and Pinot Noir for reds.

Their terroirs differ, as Bordeaux is characterized by more uniform gravelly or clay-rich and limestone soils, with a weather pattern influenced by a maritime climate and the Gironde estuary, as well as the Dordogne and Garonne rivers. While Burgundy is renowned for its diverse soils and climates, with ancient monastic traditions meticulously mapping out vineyard plots to capture the subtle and unique differences of the various terroirs.

Their cultural representations differ as Bordeaux is often associated with the bourgeois, dirigiste spirit, a more structured, serious approach to winemaking. While Burgundy is more commonly seen as representing a more peasant, sensual, and Rabelaisian aspect of the French soul, it produces aromatic, full-bodied, and sophisticated wines.

Their classification systems differ, as Bordeaux has a famous classification system that has long been a standard in the wine world. While Burgundy has a classification system rooted in medieval monastic traditions, highlighting individual vineyards, or climats, which are often smaller and more intimately studied.

In the end it is a friendly competition as While there is a clear and long-standing rivalry, it is largely a friendly one, with both regions representing the pinnacle of French wine production. Wine enthusiasts can find equally compelling reasons to appreciate both the power and structure of Bordeaux and the finesse and subtlety of Burgundy.

The choice between them often depends on personal preference and the specific occasion.

As Dany Rolland put it so well in a comment to my post on Facebook: "There are no real rivalries, but rather stories of tastes, opportunities... and these are two regions with historic, renowned vintages, which therefore fuel all the speculations of language and price, comparisons more than choices... if not cultural ones. This is the diversity."

Let's hope consumers continue to appreciate both, as both Bordeaux and Burgundy deserve to remain leaders and inspirations in the global wine market.

********work in progress*******

The post is currently in progress because it’s a controversial subject, and I want to stay as neutral as possible to avoid offending anyone, as I have worked all my life to promote both in my 33-year career.

However, if you're interested, I've already written two or three posts on this topic in recent years on my blog, as it has been a recurring subject for more than a decade.

I thought that the quote from Richelle Mead's book “The Golden Lily: A Bloodlines Novel” (2012) was remarkably insightful and very "À propos" for this illustration. 😊👍🍷

.png)

%20by%20and%20for%20@ledomduvin%202025.png)

.PNG)

.png)

.png)

%20by%20@ledomduvin%202023.png)